Centralizing vs. Decentralizing Innovation by RC Ohr

In the light of increasing demand for self-organization and organizational agility, there is a lot of discussion around centralizing vs. decentralizing ownership and decision-making – in particular when it comes to corporate innovation. Therefore, it might be useful to get back to ‘basics’, which have been well outlined by Hermann Vantrappen and Frederic Wirtz in a recent article. They suggest that the appropriate degree of centralization / decentralization depends on an organization’s goals and priorities (surprise surprise!). The simple logic is captured in the following visual:

The authors take a closer look at the four underlying qualities

- Responsiveness

- Reliability

- Efficiency

- Perennity

which is quoted as an excerpt from the original article subsequently.

(Start excerpt)

Responsiveness through immediacy. Responsiveness is all about taking the right action quickly in response to opportunities and threats. If the sources of these opportunities and threats (e.g. customers, competitors, suppliers, employees, regulators, partners, and so on) occur at the level of the operating unit, and if these interfaces are genuinely different between operating units, it makes sense to locate the corresponding tasks (e.g. sales, procurement, recruiting, regulatory affairs) and the accountability for proper execution at that level. For example, there is quite a difference between dealing with a regulator, say, in India and one in Indonesia. Decentralization allows immediacy in time and place, hence responsiveness.

Reliability through compliance. For some tasks, it is desirable or necessary to have common rules across the operating units: policies, standards, methods, procedures, or systems. Think of compensation and benefits policies, product design standards, quality assurance methods, fraud reporting procedures, financial reporting systems, and the like. These rules are meant to align the operating units with the company’s overall objectives, and make the business more predictable. Some organization unit then should assume the role of guardian: defining these rules, instructing employees properly, and monitoring conformity. It usually makes sense to assign that role to a centralized unit. For some tasks there is not even a choice: they must be done by law or statute by a central independent unit. Think, for example, of the internal audit or occupational safety functions in general, or the risk management function in banks, as the Basel III regulatory framework stipulates that this function should be “under the direction of a chief risk officer (CRO), with sufficient stature, independence, resources and access to the board.”

Efficiency through syndication. For some tasks the case for centralization is rather straightforward: a centralized unit can serve as the home for a task that is carried out more economically when aggregated in one unit than when all operating units take care of that task separately. There are various drivers of such efficiency gains:

- Traditional economies of scale. Having the same unit do more of the same task leads to continuity, standardization, specialization, leverage, and productivity. Treasury and IT procurement may be good examples.

- Minimum efficient scale. Some tasks require expertise or infrastructure that is scarce and for which demand from any individual operating unit may fluctuate over time. In that case, it is more efficient to have a pool of specialists than to replicate these in each unit. Think, for example, of legal, tax and technology experts, or costly test equipment.

- Avoiding duplication. Different operating units often have a common need for which the solutions can be (nearly) identical (e.g. an on-boarding manual for new employees, an instrument to monitor plant performance, a CRM tool). As a consequence, it is rather wasteful for each of the units to develop these solutions in parallel.

Perennity through detachment. There are certain tasks which, left to the discretion of the operating units, might not get done at all – this can be particularly true for tasks that are essential to the company’s long-term wellbeing, but do not serve a short-term function for the business units. Hence, a central unit with sufficient detachment from front-line operations may be required. Here are some examples of such tasks:

- Investments in initiatives with distant and uncertain benefits (e.g. radical innovation).

- Investments in initiatives whose benefits are contingent on everybody’s participation (e.g. knowledge management and talent management).

- Activities that involve cross-unit arbitration, i.e. weighing alternatives and setting priorities (e.g. product portfolio planning).

- Decisions to admit defeat and pull the plug (e.g. product withdrawal).

- Initiatives related to assets that are the sole property of the company (e.g. brands and capital).

(End excerpt)

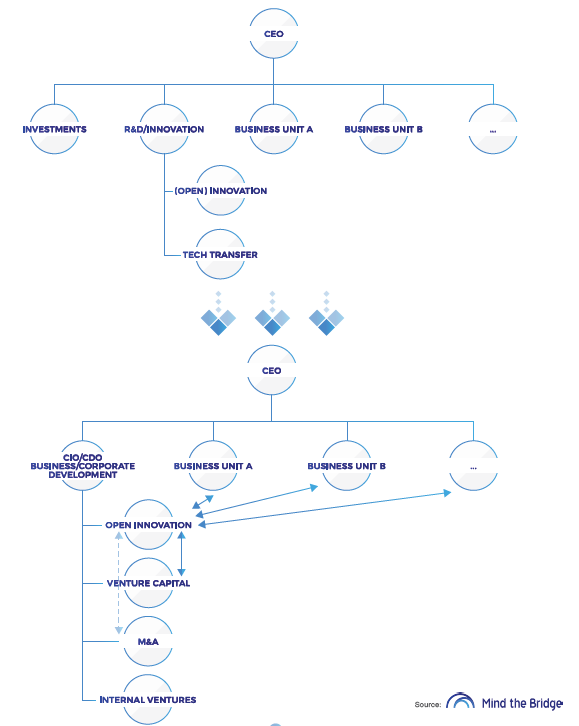

Decentralized organizational setups and structures seem to get increasingly ‘en vogue’ and certainly provide value – if applied in the right way and context. However, centralization also plays an important role in proper organizational design for corporate innovation, as research has recently highlighted. Some examples:

- Accenture has found that applying one single innovation architecture stands out as critical hallmark that sets the most effective innovators apart.

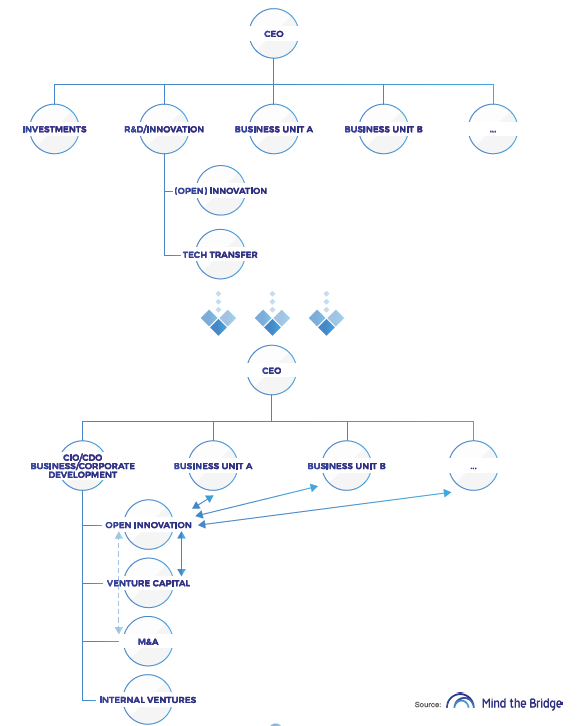

- Mind the Bridge states that 88 percent of the top corporates in the European Union run a dedicated, centralized open innovation unit.

- Vijay Govindarajan and Jeffrey Immelt call for central digital units (‘distinct but linked’) when it comes to transforming manufacturers – rather than business units decentrally developing digital capabilities that are specific to their customers’ needs.

Takeaway

In a nutshell, the following ‘rule of thumb’ on centralizing vs. decentralizing corporate innovation activities can be put up:

Centralization is indicated if innovation activities

- feature a ‘radical (vs. incremental) character‘ – associated with a high degree of uncertainty – which requires an adequate distance to and protection from the running business and their respective evaluation measures.

- are supposed to build on collaboration or ‘economies of scope‘ across different internal units (mostly together with customers and additional external partners) – as is typically the case for customer experience or platform innovation, in the course of Digital Transformations and developing new business models.

- aim at proactively responding to (potential) market or industry disruption, that mostly entails setting up dedicated, separate organizational units to accomodate and grow those potentially self-disrupting endeavors.

Decentralization is indicated if innovation activities

- address the context, scope and strategy of existing, operational business units, involving closeness to existing customer bases and drawing on established assets and capabilities, such as product and application know-how, sales & service networks as well as supply chains.

- are to be pulled off in high frequency, i.e. if the business environment is very dynamic, resulting in frequently changing customer requirements and needs (as is e.g. in the fashion or software / gaming industry).

- go along with high responsiveness to opportunities or threats and a short time-to-market.

These requirements are well factored into our modern Dual Innovation approach – which integrates the two (complementary) corporate innovation perspectives ‘Business Unit’ and ‘Corporate’. It proposes to set up a single Exploration Unit at corporate level, whose capabilities existing business units as well as new ventures can draw upon.

Source : https://integrative-innovation.net/?p=2208